What on Earth Is a Hoodoo?

When you first arrive at Fairyland Point in the mouth of Bryce Canyon National Park, you’re met by a singular sight. Mounting up from the floor of the canyon, row upon row of pink-limestone spires catch the afternoon sunlight. Each has a drippy, organic look—more like a half-melted candle than a weathered rock formation—and you’d be forgiven for imagining that they were made by an enormous cement mixer run amok. These features are called “hoodoos,” and they were eons in the making.

When you first arrive at Fairyland Point in the mouth of Bryce Canyon National Park, you’re met by a singular sight. Mounting up from the floor of the canyon, row upon row of pink-limestone spires catch the afternoon sunlight. Each has a drippy, organic look—more like a half-melted candle than a weathered rock formation—and you’d be forgiven for imagining that they were made by an enormous cement mixer run amok. These features are called “hoodoos,” and they were eons in the making.

The story of how hoodoos like these came into being is interesting. When we build man-made structures, like a bridge or building, we create by adding materials. But nature sometimes uses a different method, as in the case of the siltstone, mudstone, and limestone hoodoos found in Bryce Canyon National Park's amphitheater. They’re the result of subtraction rather than addition.

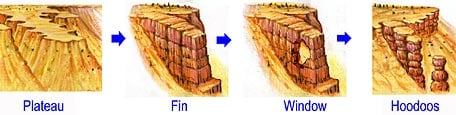

Hoodoos, which range from five to 150 feet tall, all start their geological life in the same womb—one giant plateau. Individual hoodoos are carved out over eons through the chemical weathering process, as shown in this National Park Service illustration.

These unique structures are formed over centuries as grain after grain of sediment is whisked away by water and wind. When rain water combines with carbon dioxide, carbonic acid is produced, which further erodes the limestone.

These unique structures are formed over centuries as grain after grain of sediment is whisked away by water and wind. When rain water combines with carbon dioxide, carbonic acid is produced, which further erodes the limestone.

Winter has a profound effect on the formation as well. Melting snow seeps into the rock cracks, and once night comes and the temperature drops, the water freezes, becoming ice. Water, as ice, expands, prying open the rock cracks (similar to a frost heave in the road).

Though rare, hoodoos can be found in various parts of North America and around the world. The Cappadocia region of Turkey is known for this rock formation. In France, they’re known as demoiselles coiffées ("ladies with hairdos") and a number of them are found in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. You can even find them in Taiwan, where they appear along the coast of the Wanli District.

These hoodoos won't be here forever. Erosion occurs at a rate of about two to four feet per hundred years. Though the loss of these hoodoos will come long after our lifetime, this notion can make one feel an urgency to see a geological element that, in the long run, is a fleeting one.

You can view these geological wonders on our Utah: Bryce and Zion Canyons trek. The view is other-worldly.